Malta: a breeding ground for a dangerous and repressive migration policy

Advocacy team of France terre d'asile - Published on October 16, 2025

©EUNAVFOR MED

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic led Maltese authorities to significantly tighten entry requirements for exiles. Five years later, despite the end of the health crisis, these policies remain and human rights violations are on the rise. NGOs seek to raise awareness and report on these abuses, while the European context grows increasingly hostile to the reception and integration of exiles.

In June 2025, several Maltese NGOs launched the “Malta Migration Archive“, a website dedicated to exposing human rights violations and security infringements against asylum seekers arriving via the Central Mediterranean route. For several years, NGOs have been documenting increasing cases of abuses: automatic and arbitrary detentions (including of minors), lack of access to legal and administrative assistance, pushbacks, failure to assist people in distress at sea, inhumane living conditions in reception centres… A report by the European Council on refugees and exiles paints a grim picture of the treatment of refugees in Malta.

Meanwhile, NGOs are speaking out against the racism and discriminations that are spreading in Maltese society. In 2019, the murder of Lassana Cissé, described as the first racially motivated killing of an exile in Malta, shocked the whole island. Two Maltese soldiers opened fire on a road, killing Lassana and wounding two others. They later admitted to shooting the victims “because [they were] Black.” In 2024, the sudden arrest and detention of dozens of Ethiopian residents, who had been living and working legally in Malta for nearly 20 years, also shocked exile communities on the island.

“Institutional neglect” and arbitrary detentions

In 2020, in their report on the detention of exiled people in Malta, the associations Gisti and Migreurop documented migration policies involving abusive detention upon arrival on the island. Zoé Dutot, who then worked on the island, testified: “The principle of arbitrary detention prevails in Malta for people who disembark.” During the pandemic, the reason stated was public health: people arriving on the island were automatically detained until they received a Covid test, resulting in detention periods exceeding the 70-day limit. While the pandemic no longer poses a serious threat to the island, the government is now referring to the same reasons to justify systematic detention. In July 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Committee condemned the deprivation of liberty of exiled persons for “prolonged periods” in “overcrowded units” with “regimes that come close to institutional neglect and that may constitute inhuman and degrading treatment.“

In March 2020, access to detention centres for NGOs and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was suspended, initially for seven days, and later extended by the Ministry of Home Affairs. Since then, NGOs, psychologists, and legal advisors have had limited access to detention centres. Only individual legal assistance is permitted and subjected to extremely strict regulations.

© Myriam Thyes, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Arbitrary detentions are sometimes carried out at sea before any disembarkation on the island. In April 2025, nine asylum seekers pressed charges against the Maltese state for obstructing their rights to liberty and to seek asylum, as well as for inhumane treatment during their detention at sea. The court recognised the violation of their rights and sentenced the Maltese state to €20,000 fines, as compensation to the victims. Those people were part of a group of more than 400 others who, in 2020, were detained on four tourist boats for several weeks, with limited access to hygiene and medical care, and no legal assistance.

Interceptions by Libyan authorities

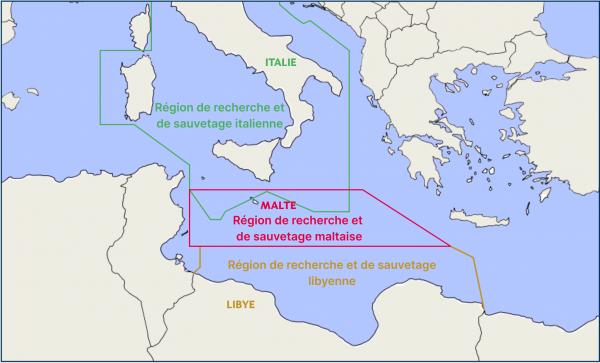

International maritime law defines several principles and obligations for coastal states: each has a defined search and rescue zone, assigned by the International Maritime Organization, within which it is obligated to assist people in need of immediate assistance. For several years, Malta has demonstrated, through its migration policy, reluctance to participate in search and rescue activities at sea within its zone – in violation of international law. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has obtained leaked documents from the European Union’s mission, IRINI, whose objectives include dismantling migrant smuggling and human trafficking networks linked to Libya. According to these sources, Malta rescued 92 people between January and October 2024, compared to 12,399 for Italy, 8,179 for Libya, and 8,271 for NGOs.

In May 2020, Maltese and Libyan authorities signed a Memorandum of understanding to establish two “coordination centres” in Valletta and Tripoli. The stated objective was to fight irregular migration in Libya and the Mediterranean, and to support Libya in its rescue operations and interceptions, thereby helping to fight human trafficking. In July 2024, the authorities of both countries signed the extension of this agreement.

This cooperation has paved the way for a growing number of interceptions of boats by the Libyan coast guard in Malta’s search and rescue zone. In 2023, an investigation by the media Lighthouse Report, looking into the cooperation between Malta and Libya, revealed the chilling testimony of Bassel. Arrested at sea and detained by Libyan authorities while attempting to reach Malta from Lebanon, Bassel described the living conditions and violence suffered by those imprisoned in Libya: physical and psychological torture, mock executions, people locked up and covered in excrement and blood, fed only every other day, sometimes forced to work to buy their freedom. Bassel told the newspaper Le Monde: “I was just wondering if I was going to be beaten to death or hanged.”

Human rights violations perpetrated by Libyan authorities in these detention centres have been widely documented by NGOs and UN agencies. In a 2022 report, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights specifically warned against “the systematic use of prolonged arbitrary detention as well as acts of murder, torture, rape and other inhumane acts against the predominantly civilian populations of these prisons, including vulnerable groups.”

The investigation also revealed that Maltese authorities and the Frontex agency were cooperating with Libyan authorities and militias, including the Tariq Ben Zeyad militia, to coordinate interceptions and pushbacks within Malta’s search and rescue zone. By providing the geographical information of vessels in distress, the Maltese authorities evaded their responsibility for maritime rescue, leaving the passengers to fend for themselves.

Border externalisation: a European approach

This cooperation reflects the will of EU authorities and Member States to externalise border management, as exemplified by the agreements between Italy and Albania, or the EU and Egypt. The Memorandum of understanding between Malta and Libya allows for the shirking of border management responsibility to this third country, before asylum seekers can even reach EU borders.

Member States shirking their responsibility can have serious consequences for the people involved. Despite the rules established by the Geneva Convention, externalisation can hinder access to asylum procedures for people in need of protection. It also opens the door to the exploitation of exiled people by third countries, which can exert political pressure on the European Union and endanger the lives of those seeking to reach Europe.

While the European Union Asylum Agency – tasked with strengthening cooperation between member states and supporting them in implementing European asylum policy – has its headquarters in Valletta, Malta’s actions are in line with those of other EU countries. Governments have been pursuing increasingly repressive migration policies that infringe upon the rights of asylum seekers. These policies have reportedly contributed to a drop in the number of arrivals on the island (from 3,406 arrivals in 2019 to 238 in 2024, and 108 in 2025 as of June 30), since interceptions take place upstream, notably by the Libyan coast guard; however, they do not address the root causes of migration, nor are they sufficient to deter exiles from starting their journey. On the contrary, they push them to adopt other migratory routes, that are often longer and more dangerous.

On another topic :

In Spain, a new regularisation campaign goes against the European retreat

Egypt adopts its first-ever asylum law, without improving the current system